As I’ve been wrapping up the year, I’ve been tempted to write an “Essay Games Top 5 Games” list of some kind. It was going to include games released this year, but also other games I had revisited and wanted to celebrate. But as I was putting together that list and looking at a lot of other excellent GOTY collections, I thought I’d take a slightly different approach.

There were A LOT of really excellent small/indie games released this year; so many truly wonderful stories and experiences made with compelling authorial voices and wonderfully crafted mechanics. And there were also “large” games―some released under the indie banner―that also caught my attention and should be celebrated for their technical craft and artistic achievement. But this year, games both big and small shared a common design sentiment that I noticed over and over: minigames as a narrative device.

Now I fully acknowledge that I might be a bit biased. Or rather, I might be suffering from the “only have a hammer” syndrome, looking at all the games of the year as minigame nails. Since my own game, Bundle of Joy (a minigame comp/romp about becoming a Dad during the pandemic, on sale for 50% off at the time of this writing!), employs the minigame as a narrative device technique in spades. It’s pretty much the whole game (besides the explicit branching narrative vignettes between minigames). So it’s hard not to apply a design fascination I nurtured for the past couple of years to everything that I see. And obviously, minigames have long been a staple of game design; they are a pillar of adventure games and open-world games, often the butt of jokes or memes within those genres (the world is on the brink of ruin, but lemme go fishing for one quick second).

Minigames typically serve as temporary interruptions to the core game loop. They are lil’ mechanical jaunts that either pad the grinding qualities of a game’s golden path, or introduce small puzzling vignettes that stimulate other neurons that the core game doesn’t touch. The hacking mechanic in Bioshock comes to mind as a great example of what minigames “do:” interject a game mode that exists separately―both mechanically and story-wise―from the central game experience while also rewarding the player by providing additional resources to reach the main (or next) objective. They tend to challenge the player to execute critical thinking skills not required in the core gameplay. As a result, they can become deeply polarizing moments for fans to contend with, often because of their technical sophistication or design dissimilarity to the core gameplay.

And, of course, there are entire games that exist as a series of minigames; this goes without saying. But what marked this year wasn’t just minigames existing in games, or that there are more of them than before. But rather, minigames are being used to convey emotional and storytelling touchstones within larger gameplay loops in a way that I think is a newer phenomenon unique to this year. In other words, we’re not getting more Wario-Ware games (though that’d be great), we’re getting new genre-bending games that use the fast-paced nature of minigames to illustrate an important element within a game’s story.

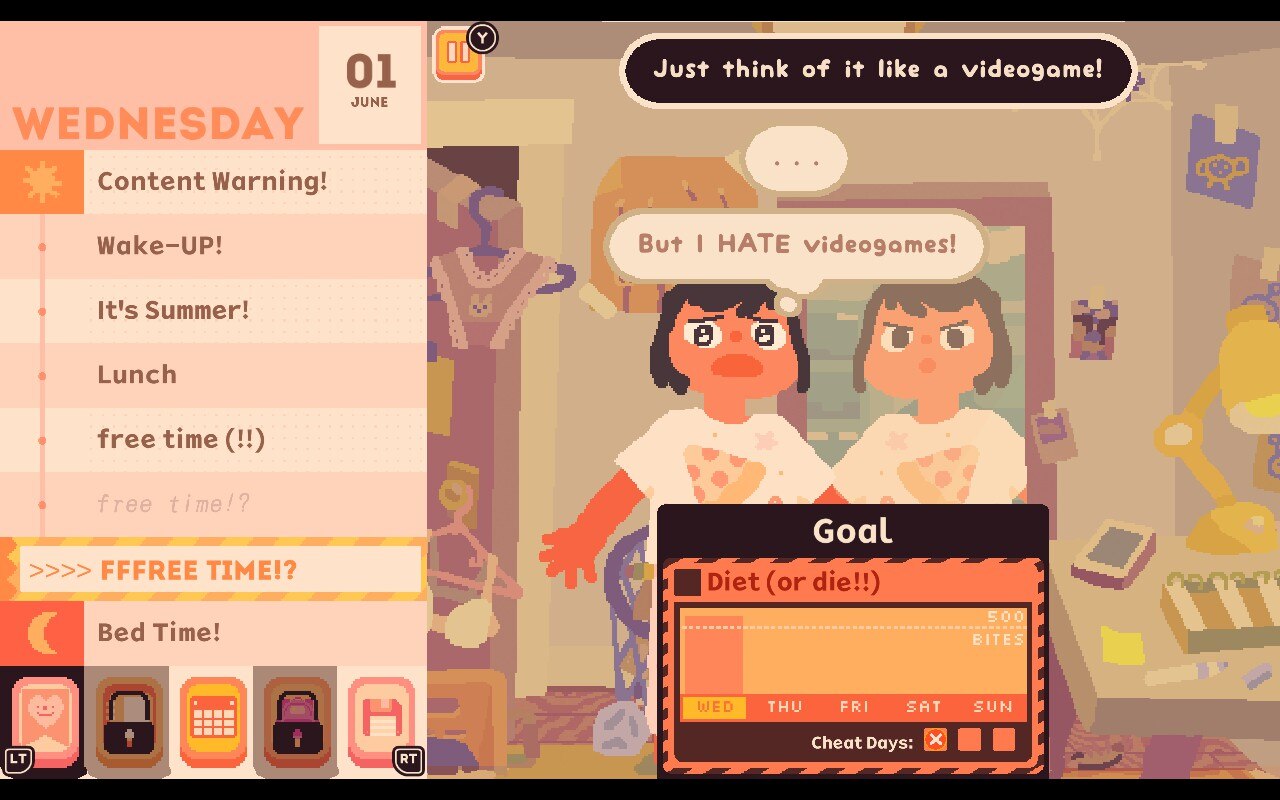

There are some obvious candidates that fall within this lil’ “trend” and at the top of the list has to be Consume Me. Jenny Hsia’s (et. all) work about body image struggles, teenage angst, and trying-and-failing to be your best self employs storytelling minigames so well. Between the button-mashing cutscenes, Tetris-like portion-controlled meals, spider-filled make-up application sequences, and a whole slew of other short-but-sweet mechanics (that’s a lot of hyphenated phrases), Consume Me uses minigames to convey the hectic and scatterbrained challenges that teenagers face, especially when trying to assert their identities within overbearing traditional family units. Though the game also employs standard dialog, monologue, description, and other visual storytelling motifs, the emotional thrust of the game comes from the rapid succession of tasks the player must perform and choose to meet a growing pile of social and self-care goals. As the house-of-cards of self-improvement collapses, and the toxic side of dieting and beauty standards takes full shape, the player-character finds catharsis in almost “under-performing” these minigames, instead opting to find solace in the journey of self-care rather than the result.

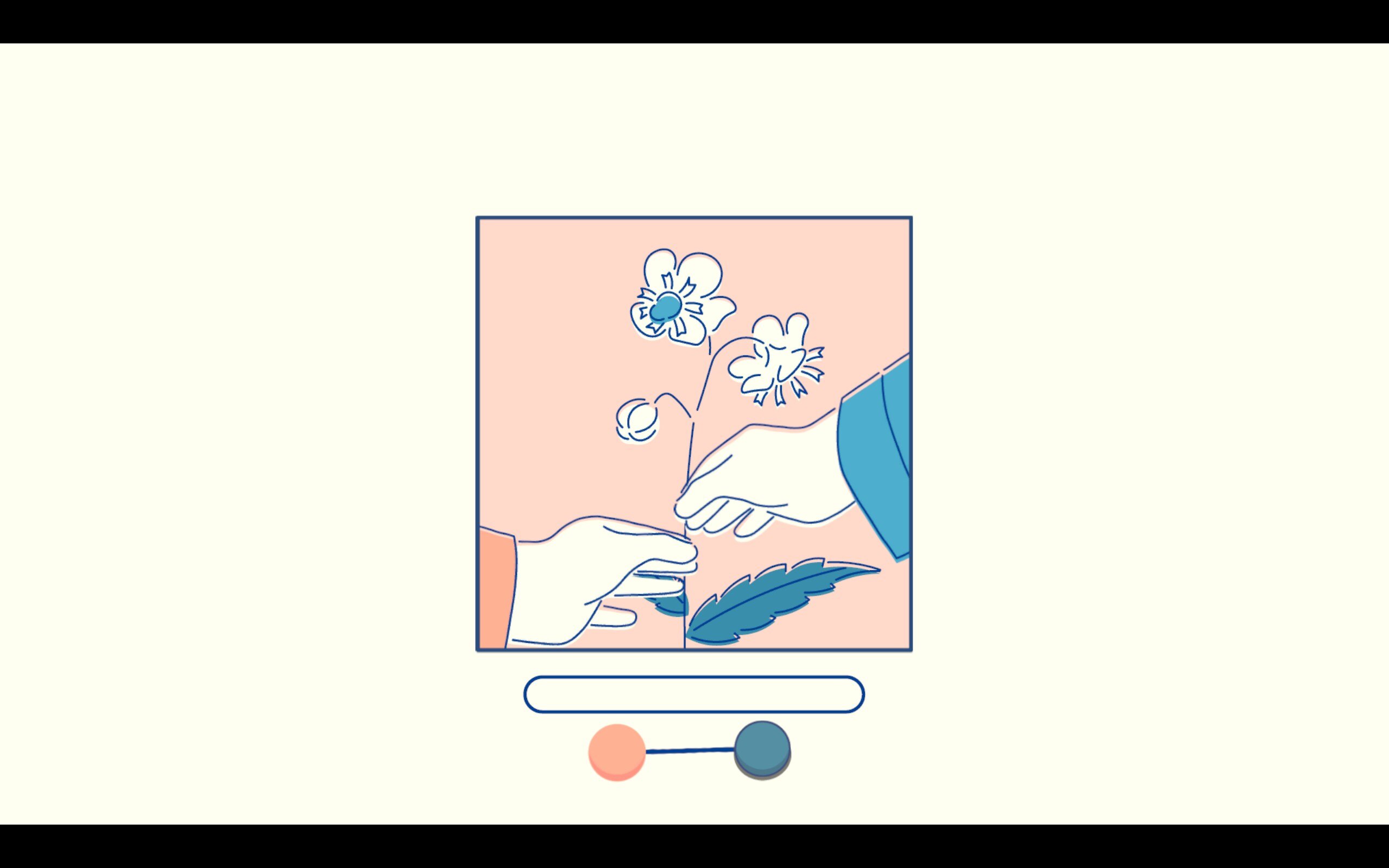

Another notable highlight that continues this trend is and Roger, the light-on-text-storytelling game that carries significant emotional heft. If this game is on your wishlist and you want to avoid any spoilers of the game’s central conceit, scroll past this section, because it’s hard to discuss how the minigames and interface-centric storytelling work without giving away some of the plot. When I first started playing, I was substantially confused by the scenario. This was, of course, on purpose. What you come to find as you explore the light puzzle design and match-making minigame “panels” is that the central protagonist suffers from a form of dementia.

and Roger leverages the effect of minigames being confusing, disorienting, and sometimes difficult to understand to put the player directly into the mindset of the senile playable character. That feeling of disorientation, of feeling lost, of not fully being yourself, and the strong desire to “solve the puzzle” that propels this piece all resonates with the bittersweet reveal of the players’ deteriorating cognitive state. The emotional complexity of mental instability is neatly mirrored with minigame designs that ask the player to “fill in the blanks.” Complete the line to make a connection with your caretaker/partner, move these sliders to focus on your bemuddled reflection, pop these radio buttons to protect yourself from uncertain and imagined threats. What surprised me was the range of emotions that and Roder presents. How the simple mechanics evoked complicated feelings and revealed a sensitively told story about loss, grief, guilt, and compassion was not only unexpected, but in the end, profoundly engrossing.

Even the deeply debated and discussed game Horses by Italian art house game studio Santa Ragione has minigames that convey the dread, helplessness, and oppression at the core of this experience. The player is presented with “tasks” that the protagonist must complete while the dead-eyed tyrant-farmer is out for the mornings. By picking flowers or vegetables, performing small fetch-quests, and other order-of-operation vignettes, these minigames reinforce the story’s dire, and―in my opinion―hamfisted themes.

The design of these minigames are different not only in their simplicity, but also in effect. They are dull and almost too game-y for the allegorical content of the work. They almost don’t fit within the overall story, but they mechanically serve a crucial purpose by being a smoke-and-mirrors preoccupation while the story unfolds away from you. Unlike other minigames I’ve noted, these require next to no skill. But instead, they condition the player into a kind of mental paralysis: do the job, even if the job is grotesque and abject. Minigames are a foil for Santa Ragione to critique route gameplay as a tool for desensitization. They don’t necessarily change/affect the story, but they certainly steer the player toward the aesthetic goals of Horses.

As a final, yet truly non-exhaustive, entry into this category is maybe my GOTY: Despelote. Though I’ve written about it already, Despelote still lingers in my mind as a gameplay experience like none other this year. How it fits within the minigame as a narrative device trope I’m outlining isn’t as clearly delineated as the titles mentioned above. As stated, minigames typically serve as temporary sidetracks to the core gameplay, but in Despelote the “minigame” persists throughout the experience. As you interact with the world, you’re constantly dribbling a ball with your feet, chasing it across schoolyards and neighborhood plazas, weaving between family members and friends. Playing footie for the majority of the game puts you into the obsessive-to-the-point-of-distraction mindset that designer Julian Cordero intends. You can’t let the ball go; you can’t not play; football is a part of you.

And as you shuffle around town, you find challenges and distractions to occupy your busy feet and wandering mind: stacks of cones, lined-up bottles on a concrete ledge, goals with inviting empty nets. Though not required, these set-pieces invite your child-like curiosity and spur plucky, yet anxious, feelings. The minigames―or better, the constant minigame―of football structures so much of the emotional tone in Despelote that you look for it everywhere. When it’s not there, you feel lost and restless, pining for school dismissal, parental release, and willing playmates.

Although I couldn’t help but observe this trend, I don’t think it’s going away anytime soon. Looking ahead in 2026, I can already see signs of minigame as a narrative device peaking its charming head around the corner. Games like The Water Museum’s About Fishing, or House House’s Big Walk immediately come to mind. And I wonder how (or if) games like Mindwave, a much more traditional Wario-Ware-like, will use the frenetic pacing of the genre to experiment with narrative. Either way, I can’t wait to see how minigames will shape interactive storytelling in the following year and for many years to come.

Leave a Reply