Below is an edited/condensed preview of a talk I’m giving at Narrascope on Saturday, June 21, 2025. I haven’t included all of my slides, and I’ve removed some bits before delivering my presentation (I know, what a tease!). I’m looking forward to giving my talk and will repost the recording once the conference organizers notify me it’s archived online. Looking forward to seeing folks in Philly at the end of the week and hope y’all enjoy this preview.

This talk is inspired by becoming a parent. I have two lovely—I guess—kiddos: a 5-year-old and a 2-year-old, and they couldn’t be more dissimilar. The older one is contemplative, kind, thoughtful, perceptive, gentle, and struggled with gross motor skills as an infant. The younger is an absolute cannonball: a pudgy sphere of kinetic energy who jumps first and asks questions (occasionally through tears) later. But what they both share is love for cuddly storytime. We curl up on the couch together and read pretty much every night and again in the morning before school. And although they share a love for reading and books, their reading habits are also polar opposites.

Notably, my youngest is an… eager reader to say the least. We tend to read the same books over and over, especially as part of his bedtime routine, so he’s all but memorized the material. He often ends rhyming couplets with me, channeling his inner Beastie Boy: little bo-PEEP, has lost her SHEEP, etc. But contrary to his angelic, mostly silent older sibling, my youngest often grows impatient with my reading speed. To make matters worse, he’s still beholden to my dulcet tones—which I have honestly fantasized about turning into a full-time YouTube channel—so the only way he knows how to affect the pacing of our nighttime sagas is to insist we move things along by aggressively reaching for the next page.

Now, as any parent might attest to, this isn’t even in the top 50 most annoying things my beloved lil’ toddler does on a daily basis. But the regularity of his impatient reach can render me a lackluster reader. When you don’t know if you’ll get a chance to finish the page, it becomes kind of hard to “commit,” y’know? So, at my weakest moments, I tend to let my kiddo take the driver’s seat and determine when & where to read.

So what the hell does this have to do with narrative design and interactive storytelling, you might ask. Truthfully, not very much, I just like to talk about my kids. Kidding aside, I was initially wowed by my cuddly, drowsy smartypants. Even with his cursory reads, he could piece together story beats and recount back to me memorable moments in the morning. But as this behavior continued, and as I saw it expressed over many different books, I began to wonder if my child’s literary sophistication wasn’t actually just the result of very good “design.” And thus the origins of this talk were born.

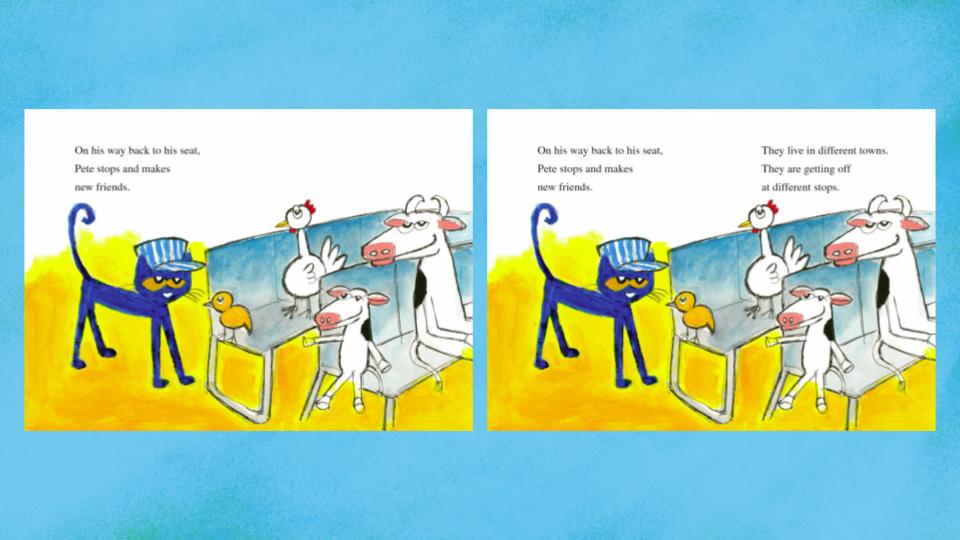

What I saw in my child’s reading was that you could essentially skip every other page and still get the full extent of the story. It’s kind of hard to conceptualize for adult readers (and designers), so let’s take an example from a book that’s regularly in our reading rotation: Pete the Cat Rides the Train. So if I read this book like my toddler, can we at the very least follow along? I’d argue that we get ENOUGH of the story to know what’s happening, we can follow the sequence of events, and understand the overarching story “flow.” But what’s missing from my son’s “edit”? Details. The skipped-over content doesn’t turn Pete’s train ride into nonsense, but it does leave out fun encounters and characterization. The core story is maintained, readers like my dear boy are given direction or “motivation” to use design terminology. But the depth of the story is missing.

The hurried reading habits of my sweet baby boy gloss over what I, as a writer and designer, would probably have spent the most amount of time poring over. It’s in those details that I really like to work. What I saw, however, was that my flesh and blood was maybe not as interested in those details as I was. In truth, what I witnessed in my page-skipping toddler was a glimmer of begrudging familiarity. I saw an impatient gamer button-mashing to skip through detailed narrative.

And listen, we’ve all been there. We’re sitting down with our Switch, our Steamdeck, or our preferred retro handheld console. We flip it on, load up a save file, remember where we left off, and dive right into gameplay. Then, some pesky NPC starts TALKING to us. They’re probably saying something really important and expertly crafted, but we’re holding down the X-button to load, advance, and skip through whatever they’re saying. We want to get back to “the action.” Especially when we have so few hours in our increasingly crowded days, we don’t want some lore drop to get in the way of leveling up or whatever.

But as a designer, the thought that anyone would want to skip over my lovingly crafted narrative makes my skin crawl. Watching my progeny committing this horrific offense was a betrayal of the highest order! How could he?! Doesn’t he know Papa loves details in storytelling?! Now, understandably, I’m not entirely sure that Pete the Cat author James Dean shares my writing preferences. Needless to say, the story of most Pete the Cat adventures doesn’t contain branching narratives or variable-based logic. However, I do think that the details are still important in Pete’s tale. Otherwise, why would Dean include them, right?

So what is a designer to do with a sleepy son or a trigger-happy player? There are many answers to this question, many methods available to the narrative designers and writers to tackle this conundrum. But watching my youngest, I couldn’t help but reconsider the Layer Cake technique as a possible design solution. I was initially introduced to this technique by Susan O’Connor while enrolled in her course at The Narrative Department. She attributed this technique to a former mentor of hers, Patrick Redding. Redding was the narrative director for Far Cry 2 (which O’Connor also worked on) and wondered how the complex story he wanted to craft could appeal to players who only played first-person-shooter games. At the time (and maybe to this day), the core demographic of FPS games wasn’t playing for the plot. The design challenge of creating a compelling narrative for a range of players intrigued Redding and company, and they devised the Layer Cake technique as a possible solution.

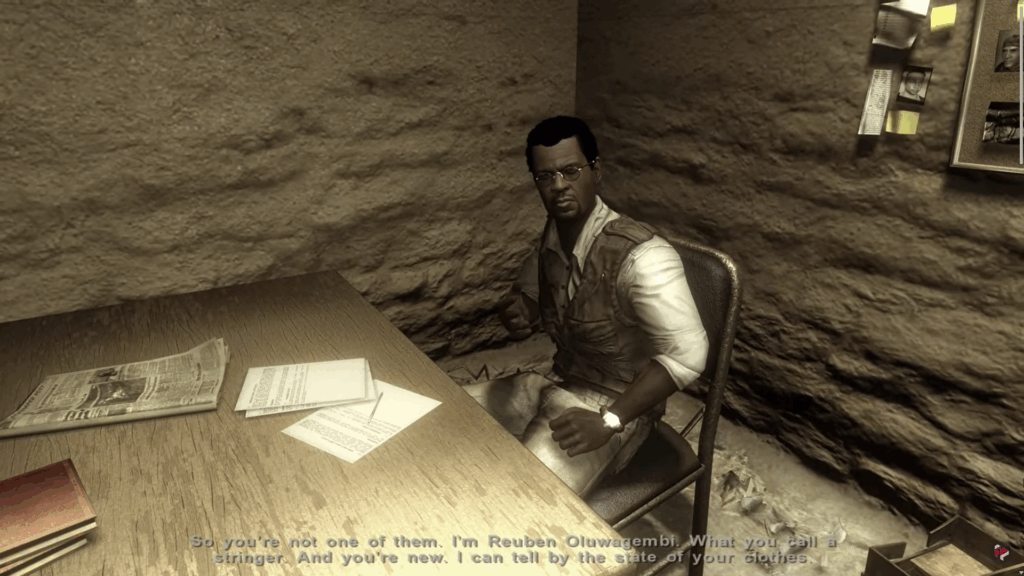

As an example, let’s look at the first time we run into the NPC Reuben Oluwagembi. In our initial encounter with Reuben, he hastily gives us a “mission” to take a recording of The Jackal—the game’s antagonist—to a priest in Pala. Doing so will help us get the malaria medicine we need. But he doesn’t even introduce himself until you talk to him the second time, giving you more details about his role, his backstory, and his character motivations. This added detail isn’t necessarily pertinent to your mission, but it does help frame the world and set up some expectations of conflict ahead.

The detail in this exchange with Reuben helps set the stage for later plot points. It establishes the NPC as a pivotal character and a trustworthy ally for gathering information and “reporting” on events around Port Selao (one of the main locations of this game). Though the interaction doesn’t have specific choice-branches like more modern games, returning to him in this scene is a choice in and of itself. This is the heart of the Layer Cake technique: the first encounter is the most basic information, but each additional encounter provides an added “layer” of detail.

Stories of all kinds have details, whether it be dense prose, nuanced inflections, or one-line descriptions. However, not all readers want details. The balance between “information” and “details” is a tight-rope walk that I struggle with constantly in my writing. Redding, O’Connor, and the narrative team understood that the story needed to be organically integrated into gameplay, and that if it was forced—particularly upon players not used to narrative-driven content in FPS games—then the underlying messages they wanted to convey might deter players from engaging.

The Layer Cake technique not only provides “gun-ho” players to get the immediate information they need to advance progression, but rewards interested players with additional details that enrich gameplay. In a subtle design maneuver, the Far Cry 2 designers show the player that an engaging story—as we all know—makes games better; when you offer details, you offer more opportunities for a deeper connection to their experience.

Leave a Reply