I’ve had time between projects to play some games in my backlog. One of the first things I wanted to get to was Chants of Sennaar, partially because I’ve been so curious about the game since it first played a demo at the IGF pavilion at GDC last year, but also because I’ve started it several times with my eldest kiddo as we’ve been exploring some games on the Steam Deck together before bedtime.

But after repeating the start of the game about a dozen times with her, I decided to shelve it so that I could give it a proper playthrough. Even upon first encounters, I knew that CoS was something special: a puzzle game that uses language, translation, inference, and contextual deduction as its central mechanic. You play as an unnamed protagonist attempting to scale a towering ziggurat that has been systematically segregated into different “classes” that all speak using different glyphs.

What initially struck me was the scale of the game. My first previews made me falsely think the game would primarily be about unlocking one system and then iterating on that system to create more complex ideas, which would then uncover further secrets/levels. But the game very cleverly asks you to build upon the knowledge of the first language to translate and interpret the language of other tower dwellers. As you move up, the game’s themes around relatedness, connection, commonality, and shared civic bonds start to take shape.

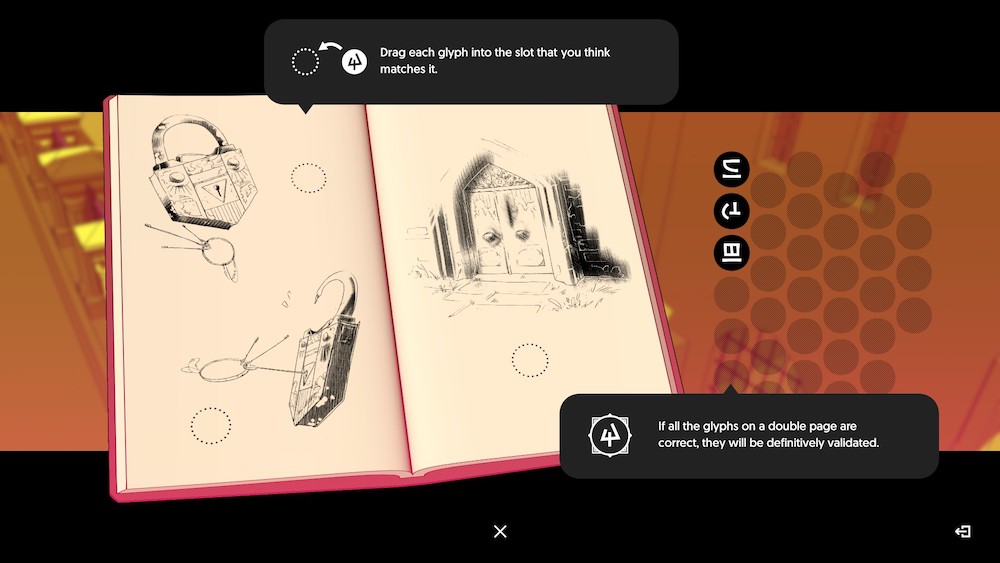

But let me back up a bit. You don’t just “get” language in CoS, the game “speaks” to you through NPCs, murals, notes, and other written ephemera and it’s your task to take notes in-game about what you’ve read and assign placeholder words to progress through conversations, puzzles, and small timed platforming challenges. Once you’ve seen words repeated, the game prompts you to name activities, actions, and objects based on your contextual notes. Once successfully translated, it gives words a more “set” definition, and you can “read” the language in your environment to overcome communication obstacles/mysteries.

Reading back this description to myself makes the game seem a bit pedantic. But there are genuine moments of revelation where you begin to piece together words based on how they are used and understand how to perform tasks, retrieve objects, complete mini-quests, and solve puzzles without fully understanding what you’re reading. Even when you haven’t completed the translation prompts in your in-game journal, you can still start to piece together phrases and relationships based on well-designed contextual clues.

CoS, at its core, unfolds like a semiotician’s puzzle box. Words (or signs) only have meaning based on their context (signified). Language is indeed a network of associations (a la Ferdinand de Saussure); objects and actions are defined more by what they are NOT than what they are. In my notebook, I’d routinely label glyphs with completely wrong words, but with very accurate context. For instance, I distinctly remember writing “zealots” when the correct translation was “chosen.” Such a distinction is not only important within the game, but says something about my relationship to organized religion.

Where this becomes even more complicated, and fascinating as a player/writer, is that the contexts shift as you play through the game, and different words/glyphs take on new meaning. Tools become Weapons, Guards become Warriors, God becomes Duty. And then certain words disappear altogether: War makes way for Music, Drama gets replaced by Gold. These substitutions make translations a bit tricky, since certain parts of the tower don’t have words for things you’ve previously translated. But apart from the design considerations, these changes reflect how language mutates, shifts, develops, and changes depending on culture.

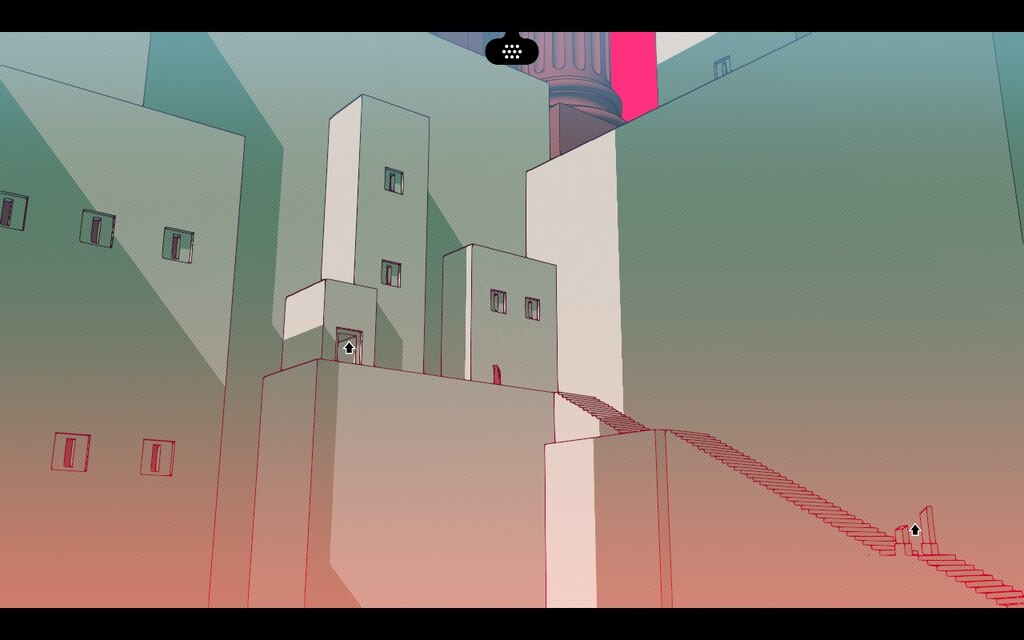

This is beautifully articulated in the different levels of CoS. Each has a distinct color palette, architectural features, NPCs, and (for lack of a better word) flavor. As a result, each level has particular linguistic challenges: some levels have different grammar, some levels have glyphs for designating plural tense, some levels have tense sneaking sections, while others are more free-roaming. How the language reflects the culture of each level is such a pivotal design detail that seamlessly enmeshes itself into gameplay. That synergy between concept and design is so well executed that it makes the narrative–which takes a bit of a backseat for a lot of the core gameplay–so legible, relatable, and impactful.

The story of CoS is probably familiar to anyone who’s heard of the Tower of Babel. To confront God, man builds a tower reaching into the heavens, showing the undeniable strengths of humanity when banded together toward a common goal. Instead of rewarding the ingenuity and collectivity of his creation, he punishes the hubris of humans and scatters the people, cursing them with new tongues that hinder communication, and thus fracturing community. It’s a strange parable when you think about it: God chooses conflict over unification, smiting the will–albeit confrontation–of the people to assert domination. To flex His superiority, He creates otherness: differentiated cultures that struggle to find commonality based on preconceived notions of who belongs and who doesn’t. The Tower falls, and humans never find a way to recover their shared glory.

You could fill a library with literary criticism, theological texts, and creative interpretation based on this biblical story. Where CoS contributes to that litany of voices is in the cleverness of its apparent simplicity. It never gets too high and mighty, and always stays grounded with simplistic tasks and manageable challenges. The adventure never strays too far from its central design, and even when the player is presented with a brand-new set of glyphs on a new stage, one never feels lost.

[SOME SPOILERS NOW!] All this being said, the really interesting bits of CoS unfold near the game’s conclusion. As you ascend toward the tower’s apex, you eventually arrive at a desolate, gray, foreboding area where the local individuals self-identify as “exiles.” These exiles have been imprisoned by an elaborate machine that keeps residents placated by offering (or forcing) headset-like simulations of “happy places” and competitive multiplayer sport simulators (or MOBAs, depending on your perspective, I guess). Though exiles communicate a desire for freedom from this tyrannical-mechanical overload, they also readily submit themselves to its technological offerings.

It’s in this moment where CoS cements its powerful message. The game up to this point has made a compelling argument for bringing people together, for breaking down the artificial barriers between tiers of the tower and dissolving an imposed hierarchy that no one seems to fully understand (though the warriors seem content to enforce). But it’s not until you reach this moment that the game crystallizes what lies at the root of all this discord. It appears that technology has been the culprit all along. The advent of sophisticated technology and its development have fractured people from one another, creating a culture where individuals self-identify their alienation, but have no means of breaking free from their technological binds. They express aspirations for unification, but cannot unglue themselves from their devices long enough to tackle their predicament.

Funnily enough, the tools to their salvation lay easily within their grasp; translation kiosks are littered about that easily unlock the exile’s language with other residents of the tower, but these devices are dormant due to distraction. The culmination of CoS presents a poignant critique: entertainment media (and games more acutely) are an alienating agent for presenting false narratives of otherness. Faceless technological entities gain power and influence by maintaining these false narratives, and they express this most effectively by distracting people through everyday passive consumption.

Language in CoS is just a red herring to get at a deeper critique of technological power. Technology, like language, requires translation and stewardship. It requires maintenance and support. Without it, technology can quickly become weaponized to marginalize individuals and segregate populations into artificial castes. CoS presents this critique so sneakily (but also so candidly) that it appears obvious once players arrive at its reveal. Of course, an artificially intelligent machine is manipulating these people. That’s just what technology does.

But this subtle send-up is so refreshing to see in contemporary games, especially because it casts its own medium/technology as being part of the problem. Such a critique would fall flat if the game itself weren’t trying something unique and inspired. Once you’re in its loop and are seeing the world through its lens, the designers could have easily left it at that: an engrossing adventure-puzzle game about language and translation. But instead, designers Julien Moya and Thomas Panuel offer something more complex and ingenious. They opt to make a game that can reflect on its place within a larger industry and communicate a message of warning directly to the player in an impressively deft, subtle, and intelligent way.

It’s been nice revisiting (and completing!) games that have taken a back seat while finishing my own projects. I look forward to finding more inspiration in my backlog in the coming weeks and sharing thoughts here.

Leave a Reply