As I mentioned in a previous blog, I want to do a couple of post-mortem posts about Bundle of Joy and talk about the experience I had with making my first capital-C Commercial Video Game. Initially, I wanted to discuss the concept, ideation, process, and some behind-the-scenes design. But instead, two recent articles motivated me to kick things off by writing about “product performance,” or more specifically, how the game has done as a commercial product.

The first inspiration piece was an article on Game Developer by editor Chris Kerr with the encouraging headline “It’s okay to make a small game.” The quote is attributed to Astro Bot director Nicolas Doucet, and the article outlines some key takeaways from his talk at GDC about how paring down design can lead to more direct player engagement. He uses his own experience designing and developing Astro Bot as a model for other industry professionals to learn from, and the article outlines some of those inside-baseball business/craft decisions.

The second source was a short piece published in The Verge about Lucas Pope’s call for developers to make “weirder, more personal games.” During his acceptance speech for the Pioneer Award at GDC this year, Pope encouraged the audience to make “unique off-beat, experimental, creative, and especially personal games.” The article (and Pope) don’t necessarily elaborate on this further besides fairly conventional “if you make it, they will come” sentiments about being an indie.

I commend the sentiment of the central statements in these articles, and although I’ve not played Astro Bot, I’ve heard a ton of good things. As for Pope, he’s not only deserving of the Pioneer Award, but I routinely recommend the excellent process blog he maintained during the development of The Return of the Obra Dinn on TIGSource to students and technical artists/designers. However, I find that it’s very convenient to deliver these comments from the perch of (hard-earned) success.

For one, it’s hard to truly take seriously the notion that small games are OK from a studio backed by one of the largest manufacturers of video game consoles. I won’t pretend to know the ins and outs of the production of Astro Bot, but the mere flexibility to make decisions on changing the production timeline with a smaller staff is a luxury that few studios, and even fewer individual developers, have at their disposal. Not even to speak of having the financial security to make these decisions based on design intentions.

Also, small is a very relative term for Doucet. “Small” still requires 10 hours of gameplay in his eyes (though he boasts that he was able to “simplify down to 8 hours). “Small” for solo developers at that scale requires years of production, maintenance, secondary employment, and massive heaps of risk. While developing BoJ, I had to learn how to wear the Biz Dev hat as part of running Essay Games. I’ll admit, it is not my forte, but what I was able to learn by talking to some really smart (and generous) folks in the industry is that working even “smaller” than what Doucet outlines doesn’t meet the threshold of interest for most publishers. This is because 1) the team is often unproven, and 2) the risk of investing in “small” games is too high. A lot of ways that publishers mitigate the risk of their portfolio is by pushing developers to expand their “small” ideas into more substantial gameplay segments that can provide 10+ hours of content for their user base (or projected audience). This, in turn, provides the publisher some rationale to charge their customers a price point that can secure ROI quicker. Without this, the risk for investment becomes too high for most business managers.

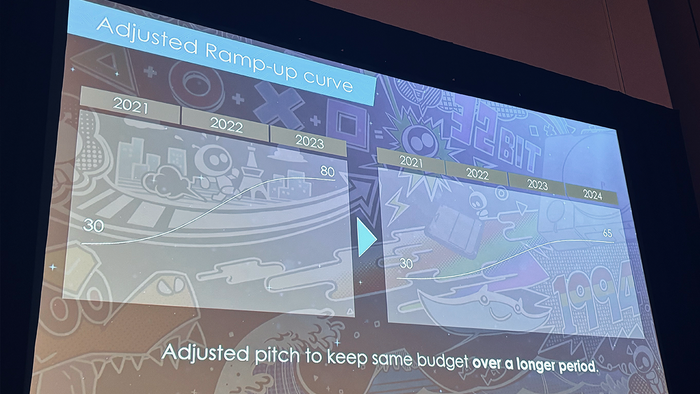

I understand that this is a bit of a blanket statement, but it is based on my experience pitching BoJ. Truthfully, I only formally pitched the game three times to indie publishers, but I sent pitch decks and requests for funds to about a dozen orgs/funders/publishers. Almost all of the feedback I got was about how BoJ was too much of a financial risk and that the <1hr gameplay wasn’t substantial enough to warrant serious consideration. Neither was my asking amount, funnily enough. Two meetings I had with publishing scouts told me that I should be asking for more money to expand gameplay and team. When I asked why I should do that, the common response I got was “it makes you look more legit.”

So… “small” to Doucet is still quite large for Pope’s truly experimental, “unique, off-beat” games devs. And, yes, it’s definitely “OK” to make small games, but does the *ahem* market *ahem* care about them? Based on how things have been with BoJ during the first month of its launch, I’d respond with an emphatic “no.”

I don’t mean to conflate the two arguments/articles, but I’ve found this ra-ra-support-indies-they-are-the-life-blood-of-the-industry sentiment to be fairly myopic when it doesn’t acknowledge larger issues of market-driven funding structures. I found that kind of messaging completely hollowed out during Balatro’s widely circulated BAFTA acceptance speech (which I’m not going to link to, just Google it, I guess). But asking for more weird games without acknowledging the ecosystem of how games are made (which these folks are VERY KEENLY AWARE OF) just makes me a bit grumpy. I don’t like dogpiling, and again, I respect these two individuals and their perspectives (Pope in particular, like I said), but the inconvenience of their statements is–to me, an individual who made a small, weird, deeply personal indie game–glaring.

This is because Bundle of Joy has been a flop. Now, I don’t want any of what comes after this to be read as any kind of “plz pity me” nonsense, or some “call to action to support me and my weird lil’ Dad-simulator.” But instead, I want to show some of the consequences of trying to do something close to what Pope and Doucet call for. Also, without going further, I want to say that I’m incredibly proud of BoJ and the work folks did on this project (Naj, Fabi, and Ethan, truly, I cannot thank you enough).

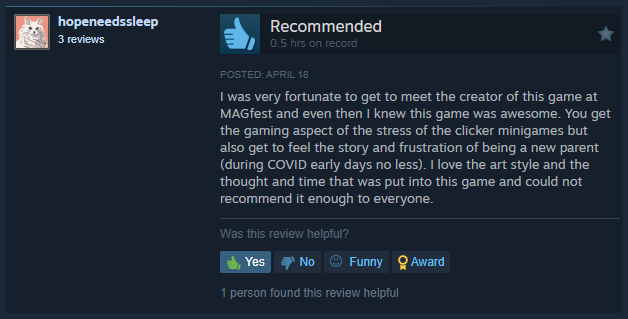

For everything that’s below, I want there to be an underlying caveat (I know, stop with the preamble) that 1) BoJ has been a success in my eyes because it delivers very well on what I set out to do, 2) I am beyond thankful to everyone that has played the game, 3) I am STUNNED by the bits of critical success I’ve accrued by some very thoughtful journalists and writers and 4) this is based on data a month out from initial release.

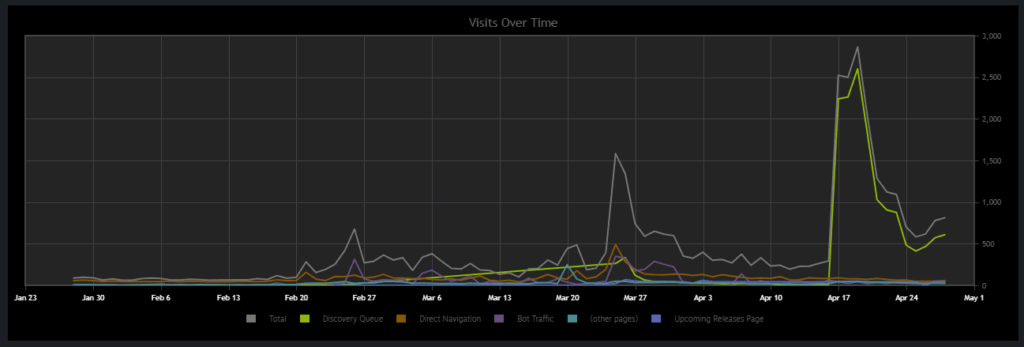

So, since release, there’s been only about 100 downloads of BoJ between Steam and Itch.io. From those downloads, I’ve netted under $1000. On Steam, my split between people who have purchased the game and folks who have redeemed Steam keys is about 50/50 (I’ll maybe get into this in another post). The game currently has 12 “organic” reviews and another 5 reviews from folks who were given a key. It also has an additional 20-ish recommendations from Steam Curators. It’s in 68 collections on itch. As of this morning, there are fewer than 1000 wishlists for it on Steam.

I spent about two years developing BoJ in its current form, and about another 1.5 years with a previous prototype. That earlier version (called The Trailing Edge for anyone paying attention) was very important for me to make, but almost none of the work from that made it into BoJ. I invested about $12K of my own money and about another $15K from friends/family investment (so amazing, grateful for that support and belief in this work). A lot of that investment went directly toward paying my amazing contractors and to supplement my income while I taught part-time. A portion of that investment allowed me to go to conferences, travel with the game, and pay for one month of additional work space leading up to the release.

Now… that sucks, lol.

And, listen, there are A LOT of contributing factors as to “what went wrong” with the commercial rollout of the game, I know. I imagine marketers looking at this data and then going to my Steam page and pointing to a lot of things that I am probably doing wrong. And there’s a lot I still PLAN to do with BoJ in the coming months to reach new audiences. But I want to discuss that stuff (the good and the bad, I promise to myself and you) at another time. I feel like just posting the above 2 paragraphs has left me winded.

But I’m sharing this (perhaps harsh) reality from the other side of “making small games” and “making personal games.” My perspective is certainly not universal, and it is truly anecdotal; I get that. But I tried, quite faithfully, I believe, to follow the advice, guides, posts, GDC talks, and resources out there for finding success within this overwhelmingly crowded market. But maybe my game is too small, or maybe, to a vast majority of the general gaming audience, it’s too personal. I’m not sure. I’ll have time and space in the future to reflect on what I did to market and share my game in a future post, for sure.

But the reason why I wanted to start here is that I want to believe what Pope and Doucet are championing. I see this sentiment coming from so many different voices across the industry, and even if I agree with it, the reality of its message can be quite an unforgiving path. Trying to create and publish passionate games that respond to these pleas doesn’t come easy. I know that this BoJ is just one singular example, a semi-sour data point in a very rocky ocean. But I know I’m not alone. I hope that in sharing this, I find others and can commiserate about what it’s like riding these wild waves of making something you deeply care about.

Leave a Reply